The meaning of freedom and security

Comparing life under "communism" and life under "capitalism" - it's less about ideology and more about financial anxieties and administrative restrictions.

In my 54 years I've lived in seven different countries, both under the communist and the capitalist systems, in "dictatorships" and in "democracies," and the lines demarcating what is freedom, what is democracy, human rights, prosperity, security, etc., are not at all clear to me. The seven countries were: Yugoslavia, the United States, Switzerland, Italy, Venezuela, Croatia, and Monaco. I've also spent months living in the UK, Spain, Austria and Germany (though without having an address there).

Of these countries, the United States is the only place where the people are regularly reminded about how incredibly free they are. Elsewhere, while people value freedom, they don’t talk about it quite so much, nor think that they live in the freest country since the beginning of creation. It's always been awkward for me to tell Americans that I actually felt much freer living in communist Yugoslavia than I did living in the United States. It's not an obvious thing to explain. In some ways, people in the United States are indeed freer than we were, but in other ways I felt much freer under communist rule.

Small, complicated rules and compliance

In part, our liberties are shaped by society's administrative rules and the way they are enforced. Under communism we had few restrictions to observe and for the most part they were enforced loosely. In many Western jurisdictions, the rules are so many, you’re bound to break a few on your way to buy groceries. This is not a cosmetic issue: already two centuries ago, Alexis de Tocqueville perceived the effects of accretion of bureaucratic rules and countless laws regulating everything.

In “Democracy in America'' (1835) he predicted that the society would fall into a new kind of servitude where the ruling authority, “covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules,” in a process which “does not tyrannise but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes and stupefies people, till each nation is reduced to be nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals of which the government is the shepherd.”

Part of my cultural shock in moving to the United States (in 1987) was to find that Americans tend to fear the police. That may be related to the fact that you could always be found in violation of some law, plus the fact that law enforcement isn't exactly lenient. My American ex-wife was always uncomfortable doing anything unless she was sure it was allowed; I can’t count the occasions when I was going to do something and she’d say, “we can’t do that, it’s got to be totally illegal!” Of course, she didn’t know that it was illegal - she only wasn’t sure it was explicitly allowed. It’s as though in the West, people have become so conditioned to police themselves that the fear of “getting into trouble” is a chronic condition of life.

In communist Yugoslavia, we had much fewer rules and restrictions. People weren’t too worried about being compliant and law enforcement was generally very lenient. In spite of that, crime rates were very low. Our streets were secure at all times of day or night. There were no drug dealers preying on young people in our streets and we had no dangerous neighbourhoods where you couldn't venture. Even as kids we roamed far and wide and our parents generally had no idea where we were. At the same time, they weren't too anxious about our whereabouts. For sure, feeling secure and free from anxiety is an important part of one's freedom – probably much more so than having the freedom to choose between Democrats or Republicans or between Labour or Tories. Consider, for example the following thread from one Denis Rogatyuk from his recent 10-day visit to China:

https://twitter.com/DenisRogatyuk/status/1814220230169915599

Prosperity and economic freedom

Another difference of life under communism was that we were less prosperous than the people in the West. At the same time however, life was a lot cheaper and in general people had no debts. Rents were symbolic, education and health care were free and our parents' modest salaries were essentially discretionary income. As a result we could afford a relatively good life which included a lot of socializing with friends and family and generous leisure time which included summer vacations at the seafront (2 or 3 weeks a year) and one week skiing in Italy or in Austria. These things were not luxuries; they were affordable to middle-income people, which was a large segment of society. In the West today, they really are luxuries, well out of reach of most people.

If we look at the 21st Century United States, the majority of Americans say they're nowhere near feeling financially secure. As we learned last month from Philadelphia Federal Reserve's survey, as many as 32.5% of respondents earning over $150,000 felt anxious about making ends meet. Granted, this may have more to do with their chosen lifestyles than unavoidable costs of living, but even in lower income groups a very substantial percentage of people feel financially insecure. For those who live with chronic money anxiety and few options in life, living in the "free world" is a meaningless blessing.

The ideologues of this same free world invariably blame the individual for being lazy, incapable, or entitled: we all know that with hard work and determination anybody can become a billionaire. If you’re not rich, you aren’t trying hard enough. But if we look at large segments of the population in both worlds, assume that they consist of a similar mix of lazy people, hard working people, and all in between, and if we measure their respective qualities of life, the differences between the two worlds wouldn’t be as clear cut as the ideologues proclaim. A family friend of ours in Croatia (formerly part of Yugoslavia), a staunch pro-Westerner who’s done well for himself in the transition from communism to capitalism said: “we’ve never had more, and life was never this bad.” Exactly: we have much more stuff today. But the quality of life has deteriorated very significantly.

Systems vs. ideologies

Last night I sat for a podcast with Tom Luongo and @CryptoRich and we went over some of these issues. I suggested that, rather than adhering to this or that school of thought and arguing why one ideology is better than the other, we may need to thoroughly upgrade our philosophical and theoretical frameworks, examine what different systems of governance actually produce over time, rather than what they tell us that they should produce, and to attempt to upgrade our societies’ operating systems.

Today we have the technologies, knowledge and information exchange platforms that were not available to any generation before us. We really shouldn’t pledge blind loyalty to 100 year-old theoretical models and force every issue into the framework they impose. Instead, we should look around for ourselves, think with an open mind and take up the challenge of building a better world.

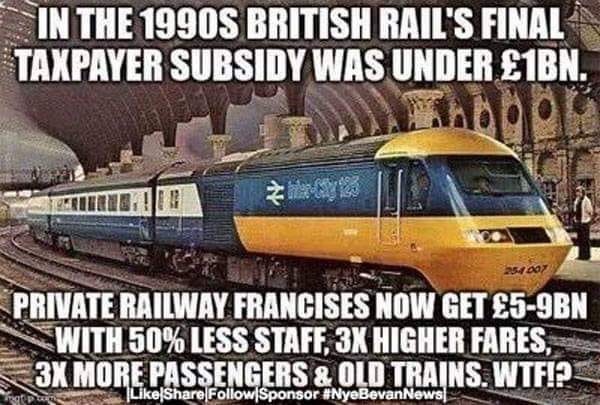

For example, if Russia and China haven’t had a single system-wide financial crisis in over 25 years, what are they doing differently? If China lifted 800 million people out of poverty in 40 years and built tens of thousands of miles of high-speed railways in less than 20 years, we should study how they accomplished that rather than condemning the CPC and dismissing their success because they’re communists. In the free market, capitalist UK, railways were privatized in the 1990s. It was all going to be super-awesome, but it’s been 30 years now and the outcome isn’t exactly a good showcase for privately owned infrastructure - quite the opposite.

To be sure, examining these issues is much harder than crying, ‘communism,’ and exalting Murray Rothbard or Friedrich von Hayek, but this is necessary if we are to improve our condition. I don’t think we have more important business here than to leave a better world behind for future generations, which should include greater prosperity and also greater liberty.

Alex Krainer – @NakedHedgie is the creator of I-System Trend Following and publisher of daily TrendCompass investor reports which cover over 200 financial and commodities markets. One-month test drive is always free of charge, no jumping through hoops to cancel. To start your trial subscription, drop us an email at TrendCompass@ISystem-TF.com

For US investors, we propose a trend-driven inflation/recession resilient portfolio covering a basket of 30+ financial and commodities markets. Further information is at link.

A "home-run" column, Alex. I've never lived outside America, but have traveled enough to know a few things. The perspective of people like you, who have lived under multiple governments, is priceless.

A counterintuitive and somewhat intriguing example of governance is the Taliban in Afghanistan. Yes, we have all been taught how bad they are but, since they formed the effective government (following the US withdrawal), they have done some intriguing things. Firstly, they curtailed poppy production (now effectively zero) and commenced a program to encourage agricultural production (during the long occupation years, foodstuffs were imported). They are well into construction of a massive nationwide canal project, to distribute water to previously arid areas, in pursuit of that goal. They are also revitalizing the Trans Afghanistan rail project (allowing the country and Uzbekistan access to Pakistani ports). And yet, to most of the world, they are the very opposite of a democracy.