Why governments can't balance their books - EVER!

Without a radical reform of the monetary system, deficit spending and accumulation of public debts will continue to accelerate regardless of who is in power. The problem is systemic.

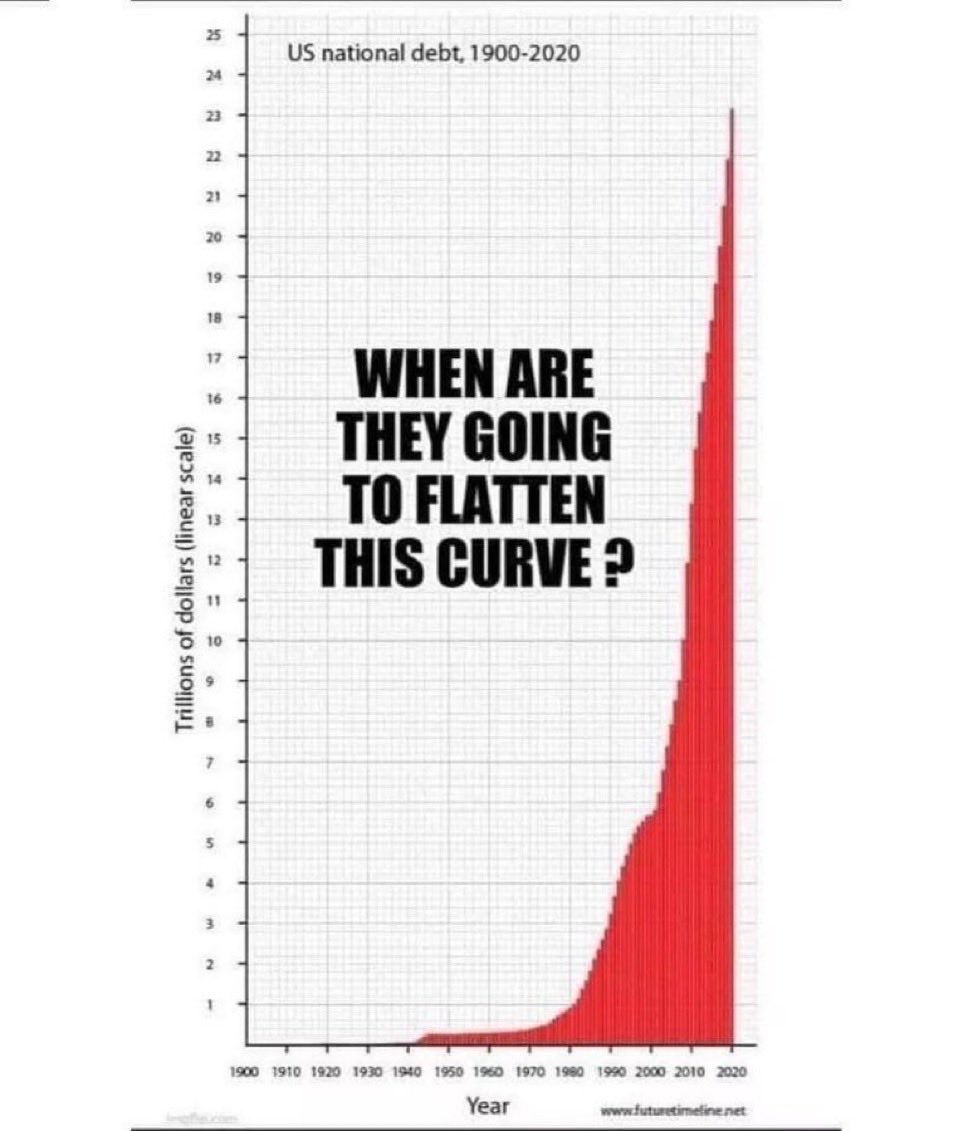

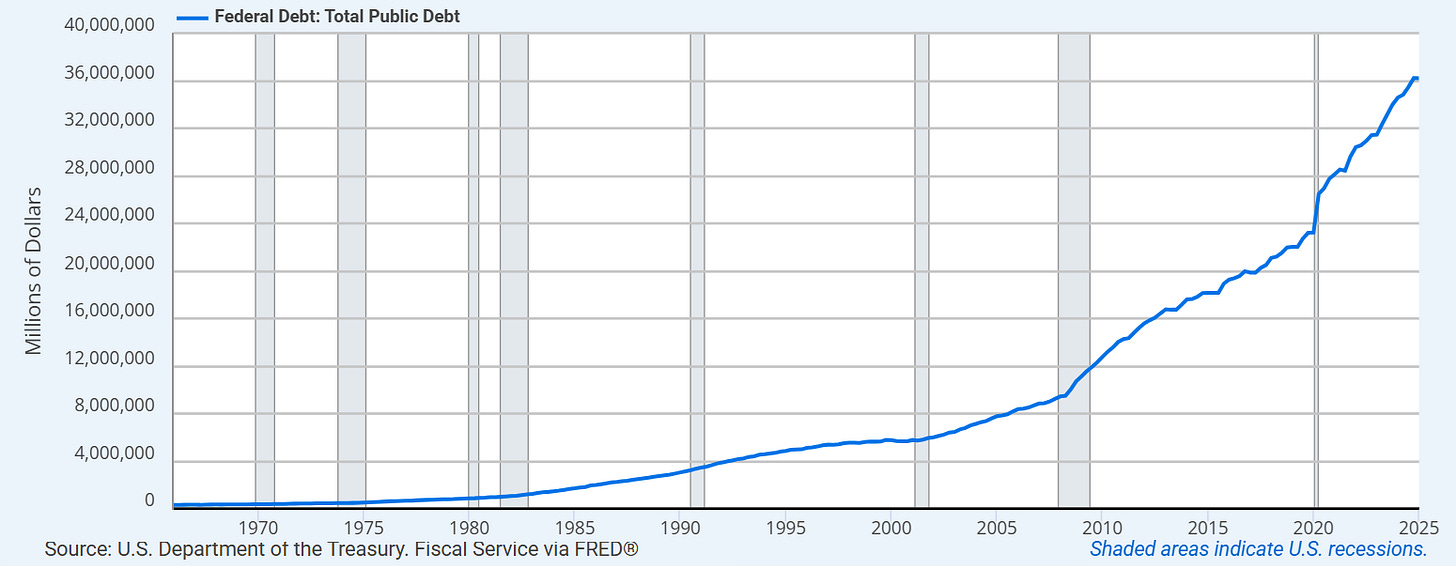

After weeks of polarizing debates, the US Senate just passed Donald Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” with opinions split almost evenly among those who want it to pass and those who believe that it will push the United States closer to its ultime bankruptcy. Elon Musk has been one of the most vocal opponents of the bill. Earlier this week, he posted the chart of US Federal Debt from 1900 through 2020 with the caption, “When are they going to flatten this curve?”

Well, I can offer a qualified answer to that question: NEVER. The qualification: unless you enact a radical reform of the monetary system. Under the prevailing monetary system, no government can give up escalating debts and deficit spending.

The curve can’t be flattened

In any given electoral cycle, conservative politicians want to cut government deficits, balance the books, pay down public debts and pursue the “small government” ideal. But for as long as our economies operate under fiat currency with fractional reserve lending, it doesn’t matter whether governments uphold conservative economic policies or whether they’re outright socialists: the “curve” can’t be flattened.

The monetary system, in fact, predetermines the outcome with certainty: conservatives AND socialists will descend along a similar trajectory to the system’s ultimate collapse. Government sector of the economy will gradually displace more and more private enterprise, the government’s role will expand, along with debts and deficit spending. All these symptoms stem from an obscure economic effect called the deflationary gap.

The deflationary gap

The following few paragraphs may seem convoluted but please bear with me, this is one of the most important principles of economics to understand, which is why it has been entirely obscured and omitted from economics curricula in all Western universities.

To understand the deflationary gap, we need to consider a closed economic system that produces a certain quantity of goods and services. By “closed” I mean that we'll assume the system has no foreign trade. The total of all the price tags attached to the goods and services produced is the aggregate cost of the system’s output: it represents the amounts of money expended by the businesses on things like raw materials, wages, rents and interest plus the entrepreneurs’ profits.

These sums are income to those who receive them and also comprise the system’s total purchasing power. On the whole, the aggregate costs, aggregate incomes and aggregate prices are all the same, because they represent the opposite sides of the same transactions. The prices at which the system’s output can be sold in the marketplace are determined by the total amount of money which is available for spending in a given period of time. For the system to be in equilibrium, aggregate prices should exactly absorb the system’s total purchasing power.

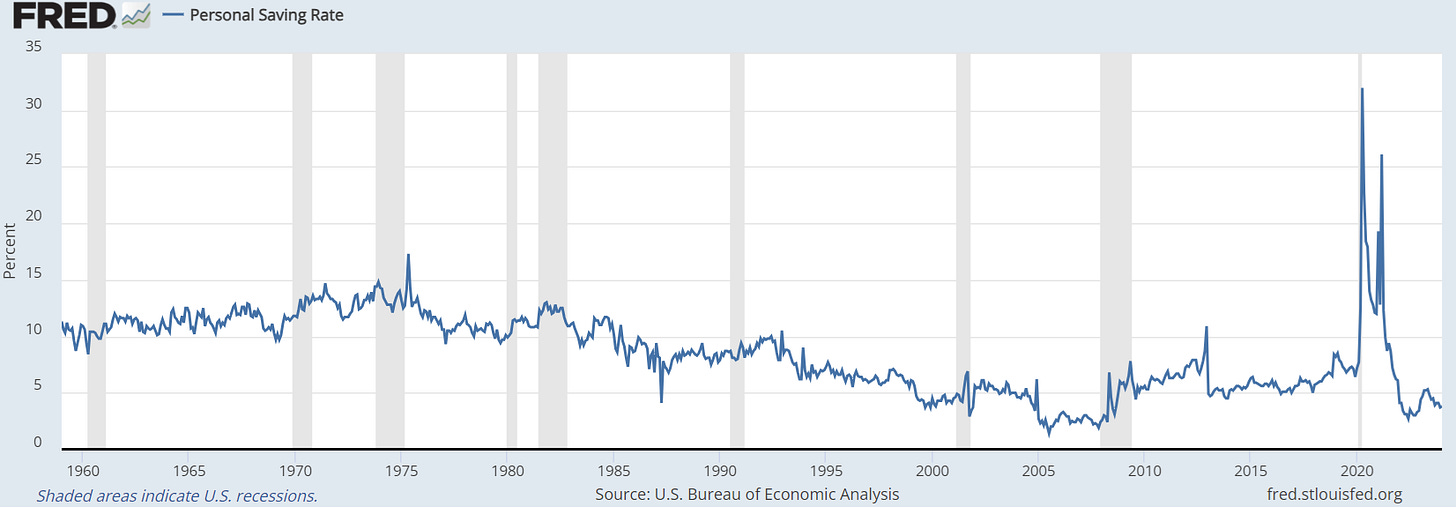

But a problem arises because in the current monetary system, there are two factors that significantly reduce the system’s purchasing power: (1) savings and (2) debt repayments. Namely, people don’t always spend all of their income. Instead, they prefer to set aside a part of it as savings which has the effect of reducing the total purchasing power available in the system.

So, if there are any savings, the available purchasing power will be less than the aggregate asking prices. For the system to remain in balance the savings would have to reappear in the market in the form of investments, but if total investment is less than total savings, the purchasing power will still fall short of the amount needed for all of the output to be sold at asking prices. This shortfall of purchasing power in the system, the excess of savings over investment is the deflationary gap.

The other systemic drain on purchasing power (hat tip to author Liam Allone for pointing this out to me) are debt repayments: since (nearly) all currency enters into circulation as debt, paying down debts extinguishes the currency and the purchasing power with it.

Without government intervention we get a depression

The system can be balanced either by lowering the supply and prices of goods, by enhancing its total purchasing power, or a combination of both. Lowering prices and production of goods will stabilize the economic system at a low level of economic activity. Increasing the purchasing power in the system will stabilize it on a higher level of activity.

Left to itself and without intervention, a modern economic system would fall into a self-reinforcing deflationary depression: the deflationary gap would lead to falling prices and output, decline of income and rising unemployment. Furthermore, in recessions and depressions, the level of investment typically declines even more rapidly than savings. To avert this, government intervention is necessary.

Without government intervention, the economy would stabilize when the level of savings declined to the level of investments which would be at a depression level of activity. This is an anathema in all modern economies, and governments invariably pursue the imperative of economic growth. To generate growth, they must inject new purchasing power into the system. This cannot be done through taxation since taxation doesn’t create new purchasing power: taxes only transfer money from those who earn it to the government.

This is why governments have no alternative but to continuously engage in deficit spending, adding debt in excess of their tax receipts. This is why virtually all governments in the world today run budget deficits and continuously grow public debt. In spite of the incessant talk about balancing the budget, paying down debts or imposing debt ceilings, the debts only keep rising at rates that predictably accelerate over time. It doesn't matter whether we call the system “socialist” or “capitalist,” they both necessitate an ever growing role of government in the economy.

Today, in many of the “capitalist” nations, government spending accounts for almost half of the GDP and in some cases significantly more. In the UK, the mothership of capitalism, the government's share of GDP is 44%. In France it's over 58%.

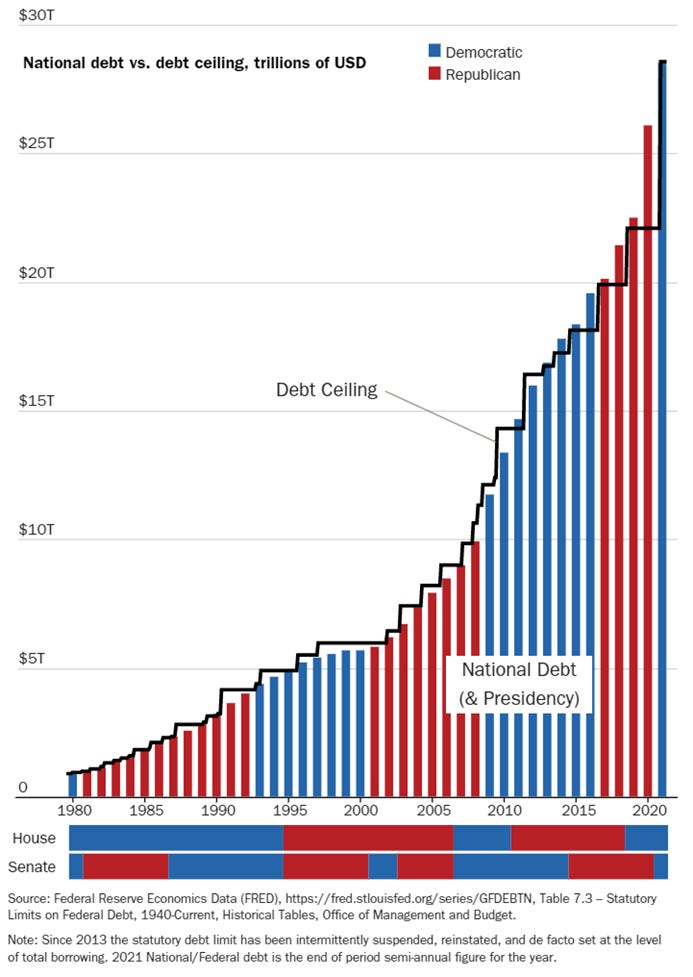

The great American debt ceiling Kabuki theater

In the United States, for over a century now we've been treated to periodic reruns of the “debt ceiling” Kabuki theatre. When public debt reaches the “debt ceiling,” free-spending socialists call for more government spending and a raising of the debt ceiling. The conservatives enjoy grandstanding about fiscal conservatism and balancing budgets, but regardless of which side controls the Presidency or the Congress, for over a century now the debt ceiling has been raised every time. The only exceptions have been periods when the ceiling was simply ignored and the public debt continued its accelerating upward trajectory:

You get socialism, whether you like it or not!

Averting depressions and achieving economic growth necessitates government intervention and guarantees an accelerating rise in deficit spending with the corresponding rise in public debt regardless of whether we are talking about a “capitalist” or a “socialist” economy. This should be obvious, as the evolution of public debt in the U.S. illustrates:

There’s no point railing against “socialism” and dreaming about a small government, private capital utopia which doesn't, and cannot exist so long as our economies are based on fiat currencies with fractional reserve lending. Even if we start with zero public debt, the pursuit of economic growth will drag the whole system along the same trajectory to ruin.

With fullness of time, the government sector will progressively crowd out private enterprise: it’s a mathematical certainty. As a result, we get socialism whether we like it or not. Even if a political leader declares himself to be an anarcho-capitalist and thinks he can create the capitalist utopia (like Argentina's Javier Millei), the endgame will be the same.

The passionate disciples of capitalist ideology will protest and invoke the theoretical works by economists like Ludwig Von Mises, Murray Rothbard or Friedrich Hayek but I would simply ask them to please name one real-world example of a successful free market capitalist economy where the government never ran budget deficits and piled up public debt. I can wait.

For those who would defend the free market ideology and excuse its failing as a consequence of human corruption and weakness of the structures of society, I’d warn them that this was exactly how Marxists explained away the failures of communist utopia. The theory is awesome, it’s the damn people who can’t get it right!

Top-down or bottom-up?

With that, we can address the false dichotomy between “socialist” and “capitalist” economies as they're commonly discussed. Namely, in what we call “capitalist” economies, a larger proportion of government-injected purchasing power flows top-down. In what we call “socialist” economies, it flows bottom-up.

Capitalist governments splurge their largesse on large private corporations in the form of subsidies and generous government contracts. Socialist governments splurge on social welfare programs like low-cost or free health care, education, generous unemployment benefits and pension plans, and programs that maintain full employment even where jobs couldn't be justified by private enterprise.

It’s what the “capitalists” hate. As a rule, individuals who strongly favor free market capitalism tend to be the successful, entrepreneurial types who value risk taking, hard work and creating wealth through private initiative. The idea that the state would splurge on the lazy and undeserving free-loaders is understandably revolting. But if you’re an entrepreneur, all those undeserving free-loaders might also be your customers, so even the hard-core business men benefit if the lazy bums have money to spend.

The alternative in governments splurging on large corporations is far more dangerous. If purchasing power is distributed bottom up, the decisions about how to spend money are up to the ordinary people. As such, they'll tend to benefit ordinary businesses that produce consumer goods and services: bakers, apparel makers, restaurants, coffee shops, musicians, tour guides, bicycle repairmen, etc.

By contrast, if the state spends top-down, it runs the moral hazard of determining the winners and losers in the supposedly free market competition. The winners will tend to be those corporations and groups that can “invest” the most in political lobbying efforts. As a result, we get the TBTF banking behemoths, big Ag, big Oil, big Pharma, big Media, big Tech and a massively bloated military-industrial complex. Ultimately, this favors the emergence of corporatism, as Benito Mussolini characterized fascism. Today we prefer the sanitized term, “private-public partnership.” The adverse effect of all this is a society’s addiction to permanent wars and a penchant for empire-building, which, by now should sound familiar to anyone who’s been paying attention.

If we want to fix what's wrong in the world today it is essential that our analysis goes past the handy but misleading labels of “socialism” vs. “capitalism,” or left vs. right, and that we deconstruct our challenges down to their essential building blocks.

The labels merely maintain an entrenched ideological divide, enabling each side to disqualify the other without ever having to stop and actually think things through. In that, the labels only perpetuate our problems and make it difficult to transcend the dysfunctional elements in our system and evolve toward better social arrangements.

With regards to today’s events, it is understandable that many on the “conservative” side want a check on government spending, an end to deficits and metastasizing government debts, but to really achieve the ideal of small, unintrusive governments, we’ll first have to do away with the fraudulent monetary system. Otherwise, all we have is a permanent clash of ideologies, fighting over labels and ideals without ever moving closer to a real, sustainable solution.

Alex Krainer – @NakedHedgie is the creator of I-System Trend Following and publisher of daily TrendCompass reports which cover over 200 financial and commodities markets. One-month test drive is always free of charge. To learn more about TrendCompass reports please check our main TrendCompass web page. To start your trial subscription, drop us an email at TrendCompass@ISystem-TF.com, or:

Check out TrendCompass report on Substack, providing daily trend following signals for 18 key global markets, including Bitcoin and gold, for under $1/day!

For US investors, we propose a trend-driven inflation/recession resilient portfolio covering a basket of 30+ financial and commodities markets. Further information is at this link.

Very clever depiction of Hayek! I suddenly want to study more of his work.

“More than 100 years ago, Lord Acton wrote: “The issue that has swept down the centuries, and which will have to be fought sooner or later, is the people versus the banks.””