Last Friday I had the pleasure of giving an interview to AnCap Radio on Twitter (AnCap stands for Anarcho-Capitalist). Among other things, the subject of trend following came up, which is my day-job. I expressed my belief that market trends are far and away the most powerful drivers of investment performance (not just a belief, there’s good empirical evidence for it, elaborated at link).

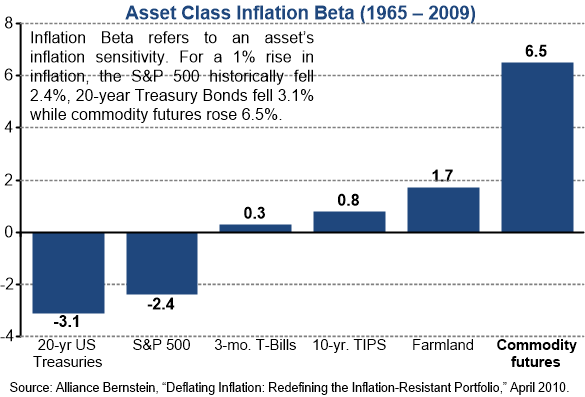

I stated that, going into the crisis period that will be marked by recession, inflation and heightened levels of uncertainty, investors should consider trend following as a strategy to navigate the unpredictable changes that lie ahead, particularly because they should seek exposure to commodities, the single best means of hedging against inflation.

One of the listeners, author and former investment banker Dr. Gert Jan Mulder brought up Warren Buffett and asked if I would agree that he's been extraordinarily successful, yet not a trend follower. Warren Buffett, as well as his mentor, Benjamin Graham are both proponents of value investing. In my formative years I studied Graham's writings and made it a habit of reading Buffett's interviews, his annual letters to shareholders, as well as books written by others about Buffett’s investing.

Well, none of that converted me into a value investor - it just didn’t add up for me the way I thought it would. In fact, in the postscript to "Intelligent Investor," Graham gave away something about his investing which, to my mind, turned everything else he wrote about asset valuation on its head.

Without Geico, Benjamin Graham would have been an utter mediocrity

Graham authored “Security Analysis” and “The Intelligent Investor,” widely considered as the most important books on investing ever written. He generated an extraordinary annualized return of about 20% over a 20-year period (1946-1966). During this time the stock-market overall returned ‘only’ about 12% per year. Warren Buffett himself generated a compound annual rate of return of over 18% during 30 years’ time. The S&P 500 index returned 10.8% during the same period (I analyzed this data in 2015 and the figures don’t include Buffett’s subsequent results).

While Graham and Buffett are generally regarded as value investors, their success had more to do with market trends than with superior value-finding skills. In the “The Intelligent Investor,” Graham observes powerful market trends as they confound his value judgment on stocks.

In 1953, as the US stock market enjoyed one of the longest running bull-markets until that point, he cautioned investors that the stock prices were getting too high. “As it turned out,” he later wrote, “this was not a particularly brilliant counsel. A good prophet would have foreseen that the market level was due to advance an additional 100% in the next five years.” By 1959, the Dow Jones reached an all-time high at 58.4, and again Graham warned investors that stock prices were “far too high.” Regardless, the Dow rose to 73.5 by late 1961 and after a 27% correction in 1962, it soared further to 89.2 in 1964.

In sum, Graham thought that stocks were overpriced in 1953 as they were about to treble in value over the next eleven years. Selling your investments before a 200+ percent bull market isn’t a good way to earn great investment returns. So how did Graham generate the remarkable results from his investments? The simple answer: by not following his own investment advice.

Instead, Graham inadvertently did what a trend-follower or a momentum investor might have advised him to do: he held onto his best performing investment even though it was overpriced from the get-go. Namely, in 1948, he and his partner Jerome Newman purchased a 50% interest in the Government Employees Insurance Company (GEICO). The $712,500 purchase was roughly a quarter of their fund’s assets at that time.

Here’s what Graham says about their GEICO investment in the post-script to “The Intelligent Investor”: “… it did so well that the price of its shares advanced to two hundred times or more than the price paid for the half-interest. The advance far outstripped the actual growth in profits, and almost from the start the quotation appeared much too high in terms of partners’[3] own investment standards.”

Graham explains why he and Newman did not sell GEICO even though they judged its price “much too high.” Because of the size of their commitment and involvement in the firm, they regarded it “as a sort of ‘family business,’ ” and maintained ownership in it in spite of its spectacular price appreciation. In Graham’s words, the profits from this single investment decision, “far exceeded the sum of all the others realized through 20 years of wide-ranging operations in the partners’ specialized fields, involving much investigation, endless pondering and countless individual decisions.”

In other words, far more than one half of Graham and Newman’s performance came from the one investment they kept through a two-decades’ bull market and did not sell it even though it was grossly overpriced “in terms of partners’ own investment standards”. That implies that all their “investigation” and “endless pondering” contributed less than 10% in annual returns, underperforming the stock market by at least 2 percentage points over 20 years.

That further implies that if Graham and Newman only invested in GEICO and spent the rest of their careers fishing and golfing rather than burdening themselves with investigations and endless ponderings, they would have done at least twice as well as they have done, generating annual returns of 40% or more from 1948 to 1966!

Buffett: a momentum chaser, not a value picker

For his part, Warren Buffett’s style reveals much more of a momentum player than value picker. He made many of his large investments on the back of major run-ups in stock prices. Examples include his investments in Capital Cities (1985), Salomon Inc. (1987 and 1994), Coca Cola (1988), Gilette (1991), Freddie Mac (1991/2), General Dynamics, (1992), and Gannet Company (1994).[5]

For example, when Buffett bought over $1 billion of Coca-Cola shares, they had appreciated more than five-fold over the prior six years and more than five hundred-fold in the previous sixty years. This decision proved right, as his investment in Coca Cola quadrupled in value over the following three years, far outstripping the S&P 500.

It’s GEICO all over again…

And like Graham before him, Buffett owes much of his success to GEICO. He started buying its stock in 1975 at $2 per share, and kept adding to this investment even as the company’s market cap went from $296 million in 1980 to $4.6 billion in 1996. This growth in valuation corresponded to a compound annual rate of return of 29.2%, an outperformance of over 20% per year more than the S&P500!

Did Warren Buffett sell this hugely overvalued company? To the contrary, in 1996 he bought 50% of GEICO making his firm, Berishire Hathaway 100% owner of GEICO. Again, not exactly a value pick, but a winner nonetheless: by 2011, GEICO’s market cap nearly quadrupled to $20.5 billion.

Even though Graham and Buffett somehow come to epitomize the so-called value-driven investing, both owed much of their success to market trends. In the American stock markets, bullish trends were out in full force through most of Graham’s as well as Buffett’s careers which were most abundantly blessed by some of their most “overvalued” investments.

Graham and Buffett may have overtly espoused value investing because it’s a rational style that sits well with investors. However, they both achieved ALL of their outperformance through momentum picks and trends and not by superior value picks.

The above was an excerpt from Chapter 6 of my book Mastering Uncertainty in Commodities Trading (free download at this link). But wait, there’s (a lot) more…

The empirical evidence

Lest someone dismiss Graham and Buffett's track records as anecdotal evidence, there is ample and compelling empirical evidence that trend following beats value investing, which I summarized in several articles, most recently in "Tesla and the Power of Momentum Investing." At some point in 2021, Tesla’s market cap eclipsed that of the next ten largest car manufacturers combined.

Between July 2010 and October 2021 Tesla’s stock appreciated 387-fold! Although that valuation would be hard to justify on any rational basis, the reality wass that Tesla had massively outperformed its peers in a trend that’s held for over a decade. If you had the wisdom and the foresight to invest in Tesla and hold it for ten years or so, you would have done extremely well.

The magic of momentum investing

But who had such wisdom and foresight? Probably not very many people. However, if you sought to systematically pick the best performing stocks and invest in them regardless of what you thought about the companies in question, their valuation, products or their management teams – there you’d be on to something… This is what’s called momentum investing.

Of course, Tesla wasn’t the only security with such spectacular valuation growth. Shares of Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, LVMH, Bitcoin and many others have skyrocketed similarly. These are not anomalies; rather, underscore an important attribute of the capital markets: they move in trends!

A very extensive empirical study covering over a century of data showed just how well momentum investing performs. London Business School researchers Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton analyzed stock market price history starting from 1900. They constructed investment portfolios by selecting 20 top performing stocks in the previous 12 months from among UK’s 100 largest publicly trading firms, and compared their performance to portfolios of 20 worst performers, re-calculating the portfolios every month.

They found that lowest-performing stocks would have turned £1 invested in 1900 into £49 by 2009. By contrast, the top performers would have turned £1 into £2.3 million,[1] a 10.3% difference in compound annual rate of return.

The gap between investments in best and worst performing stocks was even wider when data from the entire London stock market was taken into account. From 1955 onward, the top performers generated an 18.3% compound annual rate of return vs. 6.8% return for the laggard stocks. Dimson, Marsh and Staunton found that the strategy was “striking and remarkably persistent” as it proved successful in 17 out of 18 global markets studied with data going back to 1926 for America and to 1975 for larger European markets.

The significance of the this study was that it made the case that over the long term, market trends are undeniably the most potent driver of investment performance.

So, why isn’t everyone a trend follower?

It’s not obvious how to answer that question, but I believe that the problem is partly psychological and partly cultural.

It’s about narratives

Psychologically, we understand the world by means of narratives. Stock-picks always entail a narrative: this stock is a great buy because XYZ happened or will happen and this company's sales and profits will skyrocket, etc. Narratives give us something to grasp on, intellectually, discuss, debate and form a conviction. When a trend following strategy generates buy or sell signals, there's nothing to discuss, nor even a conviction to form. The basis of the decision is almost mysterious (an algo?). What's worse, an honest trend follower will tell you that there's only a 40%-50% probability that any one transaction will turn out profitable. Supported by narratives, our convictions can remain intact for extended periods even amidst draw-downs. Drawdowns may be harder to tolerate if they were the outcome of some algorithm.

To the prevailing culture, trend following is voodoo

In spite of its undeniable merit, most investors continue to regard trend following as an oddity, not entirely fit for the ranks of serious market professionals. The reason for this has nothing to do with performance but is in part simply cultural. Namely, most of today’s market professionals were educated in the Cartesian tradition which focuses on understanding linear cause-and-effect relationships that allow us to make predictions about stuff. This mindset has an obvious appeal in investment speculation: we endeavor to predict and profit from market events by understanding how the conditions we can observe would cause them. That mindset also gives us the illusion of competence and control.

Trend following is a cultural misfit in this intellectual tradition. To begin with, it is based on a field of study called technical analysis where knowledge accrues through judgment heuristics and experience rather than empirical science. Trend following also blurs the relationship between intellectual work and its expected results. The linear thinking investor judges a transaction according to an explicit understanding of how and why that transaction should generate a profit. The trend follower simply implements a set of predefined rules, accepting that any given transaction may produce a loss. A trend follower expects profits, not from any particular transaction, but from a long sequence of trades extending far into the future.

Thus, while the conventional approaches to investing stem from an understanding of a particular situation, trend following is based on the belief that a certain predefined speculative behavior will deliver positive results over time, regardless of the economic situation, industry, market, or geography. Incidentally, this is another great advantage of trend following: if you learn how to read the charts, or formulate high quality trend following strategies, you’ll be able to greatly enhance your universe of opportunities. By understanding trends, you’ll be able to trade securities even if you don’t know everything about them.

Over the last 25 years, I’ve traded in well over 50 different financial and commodities futures markets and I can confess that I know next to nothing about most of them. I merely believe that they move in trends and that with a disciplined adherence to a well-formulated set of rules I’ll be able to capture profits from such trends as and when they emerge.

Why any of this matters

These are important matters and as with most things that matter, the conventional wisdom fails to serve us. As Thomas Paine said,

“Money, when considered the fruit of many years’ industry, as the reward of labor, sweat and toil, as the widow’s dowry and children’s portion, and as the means of procuring the necessaries and alleviating the afflictions of life, and making old age a scene of rest, [money] has something in it that is sacred that is not to be sported with, or trusted to the airy bubble of paper currency.”

Thomas Paine’s slightly younger contemporary, Alexander Hamilton linked the question of money to liberty:

“In the general course of human nature a power over a man’s subsistence amounts to a power over his will.”

Ultimately, investing is about quality of life

Investing isn’t about making a quick buck speculating – it is the matter of preserving and growing our wealth, it is the matter of our life’s quality and even of our personal liberty. This is why this challenge is well deserving of our close attention and earnest endeavor to do a good job.

For investors, deciding between value investing or trend following (momentum) is a choice. But since that choice need not be exclusive, they should at the very least treat trend following as a source of second opinion. Better still, they should diversify their risk to have a portion of their assets allocated to a trend following.

Alex Krainer – @NakedHedgie is the creator of I-System Trend Following and publisher of daily TrendCompass investor reports which cover over 200 financial and commodities markets. One-month test drive is always free of charge, no jumping through hoops to cancel. To start your trial subscription, drop us an email at TrendCompass@ISystem-TF.com

For US investors, we propose a trend-driven inflation/recession resilient portfolio covering a basket of 30+ financial and commodities markets. For more information, you can drop me a comment or an email to xela.reniark@gmail.com

Investors like Warren Buffett are unlikely to operate in the fog of war of narratives and fundamental analysis like small-time players. They likely have access to unique information and possibly can influence narratives favorably. Of course I can't prove it; large, influential players would make sure their true operations are concealed. The dice are loaded against the little guy.

Thanks Alex that was awesome! I had questions as to why Buffet & Graham choose to enhance this "value investor" myth; you answered most of them. However, I do ask myself if that Value Investor myth is more supportive of the notion that Buffet & Graham are these GREAT investment minds. Being a Trend follower seems to undermine that "Legendary Investor" myth. Just a thought. I couldn't agree more with your thoughts on money. This culture tries to shame us for seeking to accumulate more money, more WEALTH. Meanwhile, many of the 'shamers' are suckling from the Gov teat.

Thanks again Alex very provocative post!